My last post for the Autism Tribune was kindly republished online by The Conservative Woman last weekend (on 22 March 2025). It stimulated as many as 124 different comments the last time I looked. While a good number of readers endorsed my argument that something serious is going on when it comes to the rising demand for Special Educational Needs (SEN) support in our schools, this was not a universal response. Several people challenged my argument that the rising numbers are real. They argued that having special needs was a ‘bandwagon’ giving individual students ‘kudos’ and allowing their parents to secure the advantages of extra time in exams and/or access to the benefit system. Furthermore, they pointed out that schools are given extra payments for the special needs kids and there are advantages in allowing children more time and support to do better when it comes to exams.

I can understand this response. It is reassuring to think that the problem is largely fictitious and more imagined than real. Just last week BBC Radio 4 broadcast daily readings from a new book that makes exactly this point. In The Age of Diagnosis, neurologist Suzanne O’Sullivan argues that we have an epidemic of over-diagnosis rather than a real epidemic of chronic disease. Her book has been widely and positively reviewed and covers the rising incidence of an eclectic mix of conditions including Huntingdon’s and Lyme Disease, cancer and autism. She highlights the remarkable increase in numbers of people being diagnosed with autism in the UK, citing a 787% growth in just twenty years between 1998 and 2018. Understandably, she suggests that this must be due to ‘over-diagnosis’ as people are more able and willing to attach themselves to the label of Autistic Spectrum Disorder.

Yet in making her case, O’Sullivan reports on the experience of a young adult patient she calls ‘Poppy’ who reported that her diagnosis of autism helped her make sense of her challenging behaviours and negative experiences. The label gave her a better understanding of her struggles to fit in, her challenges in reading social cues and inability to make good relationships. She found peace in explaining her problems as being a result of her Autistic Spectrum Disorder. For Poppy, the diagnosis was real, and I have had similar conversations with successful academics who have also been diagnosed later in life.

So too, for people now identified with Attention Deficit with or without Hyperactivity Disorder (AD(H)D) that has similarly increased in incidence and impact. Rates in children are now estimated to be as high as 1 in 20 with queues for assessments that are backlogged for years. Talking to parents, they describe their children’s problems as real. Rates of school suspension and expulsion are probably partly explained by the symptoms involved – inability to focus, getting easily distracted by other people or noise, needing constant stimulation and being attracted to danger. Even though many of the people now being diagnosed with ADHD or autism don’t appear to be visibly disabled in any significant way, it is difficult to challenge their own assessments of their condition as well as the evident distress they report.

Indeed, it is entirely possible that the rising incidence of special needs in our schools is real while it also incorporates a broader spectrum of individuals with a wider range of challenges. There are growing numbers of children with severe autism and behavioural problems like my son as well as those who appear to function more successfully but struggle with social interaction, communication and relationships. As one of the commentators suggested somewhat flippantly in response to my post: ‘It’s as though every child has special needs of some kind’. Preposterous as it sounds, maybe this person is on the right lines.

If there are changes in our environment that are impacting on our behaviour and our general health, in ways that reflect our inheritance and exposure, we might expect this kind of differentiated response. More akin to a mass poisoning event that doesn’t affect everyone in the same way, we are changing our environment with consequences that we don’t understand. Some of the responses to my post identified the extraordinary range of potential immune assaults that could be involved in our deteriorating physical and neurological health including: anti-depressants being taken by pregnant women to be passed on in breast milk; pesticides that are designed to target the nervous system of insects that then enter our bodies; industrialised and poor quality food that causes inadequate nutrition in mothers and babies; formula-feeding; lack of fresh air, sunshine and exercise; mobile phone use and electro-magnetism; family breakdown and stress; obesity; medicines and vaccination taken by mothers and children with compounded effects over time.

My son regressed into autism after having an MMR and Meningitis C vaccination on the same day when he was 18 months old. This triggered a cascade of immune problems that affected his skin, sleep, bowel, behaviour, mood and mental development. He ended up with the collection of symptoms that we call autism and I’ve written about his regression in a previous post.

It might be that pressures on the immune system are responsible for all the cases of autism and related neurological disorders, albeit at different times of onset, with different triggers and to different degrees of severity. However, this conflicts with the official characterisation of these conditions and their oversight by the disciplines of psychology and psychiatry that focus on the symptoms rather than the underlying pathology.

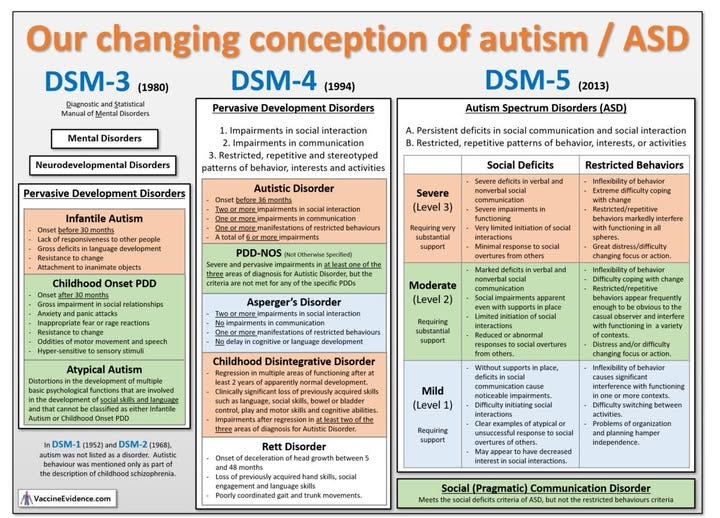

Since it’s first identification more than 100 years ago, autism has been understood as a behavioural problem that manifests in early life. It first appeared in the third version of the internationally recognised Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1980 when it was understood to be a very rare developmental condition affecting a small number of infants and children at birth or in the first years of life. Revised again in 1987, the DSM changed the diagnostic criteria for autism and characterised it as a ‘triad of impairments’ comprising deficits in: (1) communication; (2) social interaction; and (3) behaviour, interests and activities that were unusually restrictive and repetitive. A further revision in 1994 (DSM-4) included a differentiation between high functioning Asperger’s and lower functioning autism with inclusion of an additional category for those affected by a late regression in skills. This was further changed in 2013 when the three categories were rolled into one under the label of Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

This latest reclassification in DSM-5 means that people who used to be diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome or high functioning autism, some of whom can lead independent lives, are now given the same label as those who have very profound and complex needs. The changes have also occluded regressive autism or what used to be called Childhood Disintegrative Disorder (CDD).

Despite all these changes, however, the medical professionals who are responsible for diagnosing autism and other neuro-developmental conditions are still focusing on behaviour rather than underlying physiology and this is the greatest challenge affecting our children and all the families involved. If we fail to appreciate why neurological development is being disrupted, to whatever degree, we have no chance of preventing it happening in future. If we could reclassify autism as a physical condition rather than a behavioural one, we would focus on the underlying pathology and scope for treatment and prevention. While we battle over the boundaries of diagnosis, we neglect the much bigger question about what is causing the problem in the first place.

Our experience of diagnosis was a complete disappointment. After waiting months to see the ‘experts’ at the hospital we came away with a piece of paper confirming what we already knew – via google! We had all the symptoms of severe autism that followed a regression that started in the second year of his life. We naively expected the experts to have some insight into why this had happened and to investigate the obvious co-morbidities that were constitutive of his declining health and capacity. How naïve we were! Even now, newly diagnosed children are left without any follow up investigations or support for their physical health – as outlined by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the not-NICE guidelines for children with autism.

Diagnostic overshadowing means that children with autism are less likely to be treated for associated health problems such as immune dysfunction, bowel disorders and sleep deprivation than is the case for neurotypical kids. In the twenty years since our son was diagnosed, a growing body of research has produced clear evidence that backs up our experience, but this has yet to filter into clinical practice

Indeed, the parent-led charity Thinking Autism has produced a brilliant overview of the research evidence on co-morbidities in children with autism but this is yet to have any impact on the National Health Service experts and the guidelines issued by NICE. Research into the experiences of parents with autistic children undertaken 10 years ago indicates that they are diagnosed and dispatched without any attention to the underlying health problems associated with the condition.

There is, however, a parallel universe of self-mobilised parents with special needs children who are doing their best to buck the pronouncements of the professionals about the prospects facing their kids. Working with nutritionists and private doctors, parents have been achieving significant improvements in the wellbeing of their children with autism and other neurological disorders such as ADHD. Relatively simple changes in diet, bowel management and reduced exposure to toxins have made dramatic changes for us and many thousands of other parents and kids.

So in response to my critics, I would say it is best to assume that the diagnoses are real. They cover a wide range (a spectrum!) of challenges from social anxiety through to life-long disablement. Our key priority should be in finding out why this is happening and what can be done to avert it in future.

We know that the numbers of children with autism – from mild to completely disabled – are going up fast. Indeed, we know that at least a third of these children can be classified as ‘profound’ and are likely to require life-long support. The Lancet Commission on the future of care and clinical research in autism held in 2021 first advocated using the administrative term ‘profound’ “to apply to children and adults with autism who have, or are likely to have as adults, the following functional needs: requiring 24h access to an adult who can care for them if concerns arise, being unable to be left completely alone in a residence, and not being able to take care of basic daily adaptive needs. In most cases, these needs will be associated with a substantial intellectual disability (eg, an intelligence quotient below 50), very limited language (eg, limited ability to communicate to a stranger using comprehensible sentences), or both.”

Based on our experience, autism is a condition rooted in the immune system which impacts on neurological development with parallels to other psycho-neuro-immunological conditions that involve regression of some kind, such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s Diseases, Schizophrenia and Tourette’s syndrome. I was the most allergic child in my school in the 1970s (with asthma, eczema and allergies). I had antibiotics every year of my early life due to constant bronchitis. I went on to have a child with autism. His disability was triggered by vaccination but the weakness was already there in the dysfunctional immunity he had via my placenta and milk, in the disrupted microbiome he inherited at birth and in the pollutants he inevitably encountered in living today. We need to rethink our understanding of conditions like autism and go back to first principals, to understand aetiology and triggers of the condition (the ‘why’ and ‘how’) rather than just the ‘what’ as has been done for the past 50 years.

Rather than debating whether the rates are real or imagined, it is much more important to challenge the dominant paradigm that deflects us from understanding what is really going on. It is only by finding out why and how the problems occur that we will be able to treat them and reverse their prevalence. While it is comforting to blame the problems on over-diagnosis, especially if you are responsible for SEN funding for schools, I would assert that the problems are real. We need to address the environmental causes as a top priority, before it’s too late. There is a danger that we spend the next 20 years stuck in the headlights of the diagnosis debate rather than shifting to the question of what is causing the problem. This is the quest of the Autism Tribune and I hope you’ll let me know what you think.

Thanks Joanne - brilliant comment. I'm also troubled by people celebrating the identity of being autistic and over-shadowing our experiences of severe disability. However, I also think the celebrity autists are genuine. People like Chris Packham, Christine McGuiness and Greta Thunberg talk about their challenges in engaging in the world. It is not helpful that DSM-5 allowed such a broad categorisation of autism that it now includes such a range of experiences and capabilities. However, I don't want us to fight the wrong people. We could have a civil war inside the 'autism community' rather than addressing the real challenges - the rising numbers, the impacts and the need to understand the causes of the problems in the first place.

The word 'neurodiversity' makes it all sound benign and normalises what is really an existential threat to humanity. It is useful for people as a way of ignoring what is going on - and it means they don't need to look at the causes of the neurological damage. I'm building up to writing more about this in the coming weeks!

I think it’s much easier for people to dismiss this explosion in autism as ‘over diagnosing’ rather than facing the fact that something is going badly wrong somewhere along the line of their development. That thought then leads to uncomfortable feelings and questions about the existing vaccine schedule , how we feed our kids and the environment we are living in. Our local CAMHS has announced that they are no longer accepting referrals for autism diagnosis as they currently have a 3 year waiting list. What happens to the kids who can’t access support without a diagnosis? What happens to the families falling apart under the strain? Why is no one questioning what on earth is going on that so many kids are waiting on a diagnosis ?