This week I learned that the House of Lords (the upper chamber of the Houses of Parliament in the UK) has a Committee on the Autism Act 2009 that has twelve members and is chaired by the Baroness Rock. Timed to coincide with Autism Awareness Day, the committee is calling for evidence about how well the Autism Act, Autism Strategy and statutory guidance are working and what could be improved. This has prompted me to do some digging – I’ve looked at the Act, the latest version of the strategy (published in July 2021) and associated guidance. I’ve come up with some ideas to share with you and hope you’ll correct or make additions via the comments section below. I will then pass them on to the committee and let you know what happens next. If you are inclined to do the same, the deadline is Monday 2 June.

By way of background, the Autism Act was passed 16 years ago to ensure provision for adults with autistic spectrum conditions covering England and Wales. It has its origins as a Private Members Bill championed by Dame Cheryl Gillan MP and is wonderfully short and succinct. It is particularly interesting to note that the penultimate clause (5 of 6) says that any extra costs arising from the Act will be met by Parliament, something that local authorities might want to bear in mind when it comes to dealing with their current deficits which are partly caused by meeting these demands in relation to adult social care.

The Act depends on the government having an Autism Strategy that lays out HOW it is proposed to meet the needs of people with autism. It is the responsibility of the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care to prepare and publish this strategy and the most recent version, published in 2021 to run until 2026, was overseen by the Right Honourable Sajid Javid MP. For the first time, the current strategy covers children as well adults but is now only applying to England (with each of the devolved administrations in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland having their own approach).

The strategy has 6 priority areas (as copied below) with ambitious goals under each. Delivery depends on a range of government-funded organisations including the National Health Service, local government, probation services and the criminal justice system. The strategy is packed with good intentions and a plethora of initiatives that are being piloted in various places by a range of organisations but there are some very basic problems with the whole approach.

The Autism Tribune proposes to submit a response querying three very basic concerns that need to be more clearly addressed: the ‘what’, the ‘extent’ and the ‘why’ of autism.

1. What are we talking about?

First and most obviously, there is some confusion about what is meant by autism. The opening paragraph in section 1 (‘About autism’) states that:

‘Autism is a lifelong developmental disability that affects how people perceive, communicate and interact with others, although it is important to recognise that there are differing opinions on this and not all autistic people see themselves as disabled.’

Our son regressed into autism in his second year of life. Although he will now likely live with it for the rest of his life, he was not born with autism or any sign of neurological delay. Research suggests that up to 30% of children with autism fit this category with a mean age at regression of 1.78 years. This group of children used to be recognised in diagnostic protocols and were sometimes categorised as having Childhood Disintegrative Disorder (CDD). However, changes in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) in 2013 incorporated CDD as well as Asperger’s or high-functioning autism into one larger group called Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD). This has obscured the importance of regression and implies that autism is always innate.

It is also important to highlight the differences between those with high-functioning autism (who used to be given a diagnosis of Asperger’s syndrome), who are much less likely to have learning difficulties from those with severe or profound autism. This latter group are estimated to comprise about a third of those with autism and are characterised by having learning difficulties and requiring 24 hour care.

It is essential that the strategy is much clearer about these differences to help understand what we mean by autism and what might be done about it. This means clarifying what is meant by a ‘developmental disability’. DSM-V has not done any favours to the children with regressive and profound autism as manifest in my son. Indeed, it has allowed autism to get tangled up in the language of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI). People have claimed that autism is a form of ‘neurodiversity’ and it demands to be treated ‘equally’ along with other ways of seeing the world. In this regard, there is a push for ‘inclusion’ in society on equal terms with everyone else. This is pie-in-the-sky and DEI-speak serves to damage the interests of the most marginalised people with autism who are unable to speak for themselves.

Thus the neurodiversity crowd and their supporters obscure the very real disabilities of people like my son. He is not able to converse, he cannot look after himself and has no idea about socially-appropriate behaviour. He requires full time, life-long care. If we were not here to cook his meals and wipe his bottom, the state would have to look after him at enormous expense.

The autism strategy is confused about these differences and their significance for public policy and provision. Indeed, the current strategy confuses autism with neurodiversity, such as in the final sentence of the opening ‘what is autism’ section where it states: “It is estimated that around 1 in 10 people across the UK are neurodivergent, meaning that the brain functions, learns and processes information differently (Embracing Complexity Coalition, 2019).” This serves to obfuscate what we are talking about and needs urgent attention.

2. The extent of the problem

There are serious problems with the numbers being used to underpin the current version of the autism strategy. The opening text of the strategy (‘what is autism’) says:

‘With an estimated 700,000 autistic adults and children in the UK – approximately 1% of the population – most people probably know someone who is autistic. In addition, there are an estimated 3 million family members and carers of autistic people in the UK’.

These numbers been in circulation for more than a decade appearing on medical websites as well as the ‘what we do’ page of the National Autistic Society site.

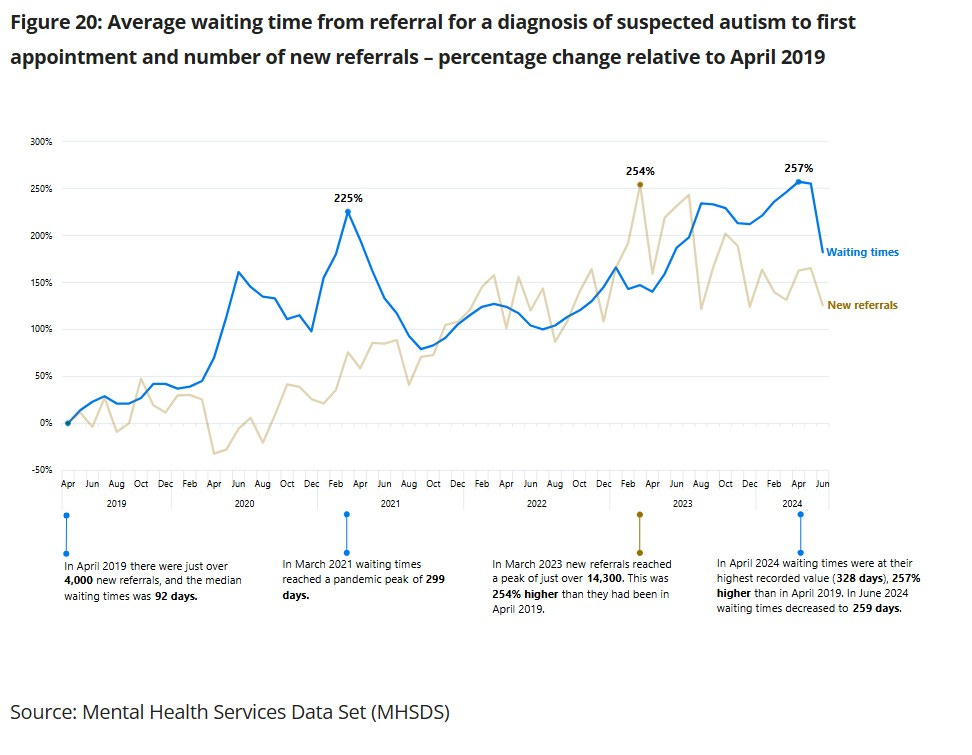

However, we know that these numbers are way out of date. Rates of young people being diagnosed with autism are now much higher than 1%. Monitoring in Northern Ireland put the rate at 1 in 20 (or 5%) in 2023 and while there is no adequate monitoring for England, the NHS collects data on the number of referrals and waiting times for assessment and these are going up year after year.

I would argue that the autism strategy is worthless without a much better handle on the numbers and the growing rate of demand. While the need for better monitoring is highlighted as one of the key ‘enablers’ of the strategy, right at the back of the document, it seems remarkable that government is not keeping better track of the problem. Indeed, everything in the strategy is about improving access to services (for diagnosis, education, employment and health services) as well as reducing rates of hospitalization and criminalisation but this activity ALL depends on knowing what is coming in future. Service mangers are expected to plan for the future to ensure there is sufficient capacity to meet this demand.

Furthermore, and going back to the previous point, managers would also need to know the mix of likely demand in relation to the different groups of people with autism and plan for the needs of each group.

3. Why do we have the problem in the first place?

Most importantly and not mentioned anywhere in the strategy is the question of ‘why?’ Rather than just accepting the rising numbers and normalising the increasing demand for services, there is a desperate need to understand why this happening. Given the current trajectory, we will be facing rates of 1 in 10 children having autism in the very near future. This is a catastrophe. No successful species has ever willingly overseen the collapse of the next generation as we are doing today. The costs to individuals, families, communities and the nation are already too great to bear and they are set to get worse.

The strategy touches on the need for research as an ‘enabler’ including it at the end of the document. However, it thereby endorses the view of the charity Autistica that “the balance of research investment has been on the basic science underlying physiological mechanisms of autism, and that there has been a relative lack of research on producing evidence on the best ways to meet autistic people’s needs, for example in understanding adult social care services that work for autistic people.” This implies that we need LESS focus on the underlying pathology of autism and more on how people can live with the condition. I disagree emphatically. We need a massive boost in good quality independent research that focuses on the causes of autism. The government already provides funding to UKRI for research into neurodevelopment disorders, much of which is spent on supporting centres at King’s College London and the University of Cambridge. These centres have yet to come up with anything that stems the rising tide of cases and future demand. Indeed, the team at Cambridge are actively diagnosing more adults as part of the broader neurodiversity movement covered above.

Any future boost to research funding should involve the parents of children with regressive and severe/profound autism as well as those who are able to speak for themselves. The interests of our children need to be considered in the allocation of research funding and the development of services.

Furthermore, there is a desperate need to integrate what we DO know about autism into clinical practice to better support people’s health. The section of the strategy covering health highlights the extent to which people with autism are more likely to have additional, often untreated, medical co-morbidities and live shorter lives than the general population. Indeed, the strategy cites research that suggests autistic people die 16 years earlier than their non-autistic counterparts.

While this is explained in relation to a reluctance to come forward for treatment and poor professional standards whereby patients’ needs are overlooked, I think there is a much bigger issue that relates to our understanding of the condition itself. Research highlights the extent to which autism is related to disruptions in the development of the immune system and the impact this has on neurological development. The charity Thinking Autism has a brilliant overview of the medical co-morbidities found in people with autism that relate to allergies, bowel function, food and energy levels (among others). If an autism diagnosis routinely triggered a thorough screening and potential treatment for these related conditions, there would be dramatic improvements in basic health and well-being for all those involved.

Rather than prioritising training for NHS staff in how to approach people with autism (and the strategy encourages trusts to follow the Oliver McGowan approach), these staff could be educated in the co-morbidities associated with the condition and how to assess and treat these. This would further require a review of the NICE guidelines for children and adults to integrate this basic training and routine assessment into NHS protocols for practice. Both sets of guidelines are currently very weak in this area and need updating in line with the latest internationally recognised research in this field. As a review published in the American Academy of Paediatrics journal in 2020 explained: “care providers should be familiar with the diagnostic criteria for ASD, appropriate etiologic evaluation, and co-occurring medical and behavioral [sic] conditions (such as disorders of sleep and feeding, gastrointestinal tract symptoms, obesity, seizures, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, and wandering) that affect the child’s function and quality of life.”

The Autism Tribune advocates that we go back to basics in order to respond to the autism crisis in England. We need much greater clarity about WHAT we are talking about when it comes to autism. We need a much better handle on the NUMBERS involved and WHY they continue to rise. Without this, there is little point in publishing ambitious strategy documents and guidance. Current demand is already overwhelming schools and bankrupting local authorities, as well as pushing families too far.

This short submission has made concrete suggestions about how the NHS and NICE could address the co-morbidities affecting the health and well-being of people with autism. In the longer term, however, it is imperative that we understand what is causing the problem and stop it from happening in future. Although it is not mentioned anywhere in the present version of the strategy, the core goal of government policy and practice should be to end the autism epidemic before it’s too late.

"it is imperative that we understand what is causing the problem and stop it from happening in future"

I couldn't agree more and as you make clear, this is not yet happening.

(Great article on autism on TCW today, thank you)